To read the first part of this article, please click on this link: https://lubnah.me.ke/before-dawn-part-1/

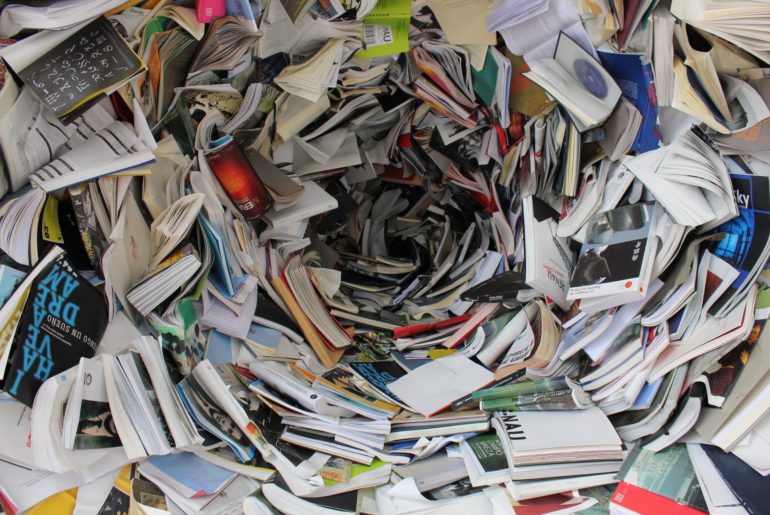

Have you realized that PP1 students, children of about 4 years only, study around 7 textbooks? And sometimes have to leave home as early as 6 a.m?!

When talking about the well-being of children, we must also talk about the draining effects of the new education system in our country.

The intention and vision behind the new curriculum (CBC) may be brilliant but the amount of pressure this system has exerted on parents, teachers, and the students has been immense so far. CBC aims to shift Kenya’s educational paradigm from a teacher-centred approach to a more student-centred one. Student-centered learning places more emphasis on skills development, a child’s well-being, and inclusivity. However, despite this new curriculum’s appeal, at least on paper, we know that there’s a lot more that needs to be done in reality. We have deeper systemic challenges that need to be dealt with i.e. teacher training, ineffective policy, and infrastructural barriers. Not to mention how these children and even the parents were not mentally prepared for all these changes. AT ALL!

Some assignments require the use of smartphones and the internet. Some require the active participation of parents for example practical making of scarecrows or musical instruments and the like. The number of lessons has increased for school children by almost double, which can be quite overwhelming. The number of textbooks plus supplementary books required in schools has been a big burden to most parents too. The reality is that many Kenyans still struggle to make ends meet let alone afford the internet. Some have to work overtime to bring food to the table such that they barely see their children let alone assist them with the assignments. What happens to these children? Or what can these helpless parents do? Weren’t all these factors to be taken into consideration before the implementation of the new system (even if we acknowledge its long-term benefit?)

We can see how bad things are by the number of children attempting or committing suicide for losing money intended for school or when achieving lower grades than expected. Just this year, students have had to attend 4 schools terms in an attempt to catch up with the time lost to COVID-19 last year, while parents have had to pay school fees 4 times too. The frustration and exhaustion are affecting many parents, students, and even the teachers to scary depths.

***

Parents too play a major role in creating emotional distress amongst school-going children. Some of them offer conditional positive regard and love on the basis of their performance or the career path their children partake. If one was lucky enough to have joined a university or a college, then there was the endless reminder of how much money (most of which were loans) is being paid for the school tuition. You could never afford to fail, or God forbid repeat a class, even if you really did your best!

There’s also the very common habit of forcing children to take up courses they have zero interest in. How many students have we heard went into depression because they were forced to study medicine or engineering despite the child’s apprehension and protests? Parents set the standards for their children based on their own personal dreams and self-fulfillment, and induce pressure on their children to do as they expect. When the children attempt to resist the university courses that their parents want them to enrol in, they are threatened with abandonment – “you’ll pay your own fees” or “please move out of my house.” Some are even ready to disown their children if they don’t follow the career path they choose for them.

Understandably, parents want the best for their children and they have more experience in life. However, that does not in any way help when their son or daughter is passionate about a different career path. It is also not helpful when the children have to suffer psychologically and emotionally in order to please their parents. So many children have had to resort to two degrees; one that the parents want them to undertake, and another that they want for themselves. Some had to drop out at some point due to the dissatisfaction and lack of interest in the degree courses their parents chose for them.

***

The struggle for young adults doesn’t end here.

After being forced into careers that they’re not passionate about, many students at the university are often faced with myriad other challenges. Even for the students who genuinely dedicate themselves to their education, university life can become overwhelming. This is the phase whereby everything seems to put one on the edge. You’re either thinking about your future, your career, or your piling, unpaid fees; and at the same time, you are thinking about the need to establish social networks crucial for career progression in the future; or worried that you haven’t seen your family for close to eight months, or missing out on forming important long-lasting relationships.

When were you ever going to rest?

In a report by the Kenyatta National Hospital that was released in 2015, over 100 cases of attempted suicide among the youth aged between 18-25 (mostly campus students) were reported within a span of two months. These numbers have escalated since the Covid-19 pandemic. Keep in mind that these are only the reported cases. With suicide and attempted suicide still being considered taboo in the majority of Kenyan cultures, many of the cases are hidden.

In a 2019 publication by The Standard Entertainment epaper, there are growing concerns over the number of young adults committing suicide. One victim of suicide was Ndirangu Mwai, a second-year student who committed suicide at his rented house outside the university premises. It is said that Ndirangu had confessed to a local pastor about his suicide plan over squabbles between his parents regarding poor grades.

Another 23-year-old student, Edwin Mwaizi, a fourth-year Petroleum Engineering student, committed suicide by inhaling carbon IV. In the note that he had left behind, he stated that he was stressing over lack of money and upcoming end-of-semester exams among other reasons.

According to someone who knew him closely, Edwin was smart and ambitious.

The surge of suicide attempts and cases haven’t only been reported among campus students. We’ve also heard quite a number of times from the news, of children at primary school level committing suicide too. In 2018, a class eight student allegedly committed suicide for not performing well in a test. The 15-year-old had been leading his fellow candidates in other internal tests. However, it is said that he came out second out of 26 with 372 marks during the second term while the leading candidate scored 373 marks. As reported by The Standard Entertainment epaper, sources said that the boy wrote on the blackboard, explaining his disappointment with his performance.

The note – “Congratulations to all my teachers who have been teaching me since I joined this school. It is not my fault to bid you goodbye but because of unavoidable circumstances, I’m forced to do so. It is useless to live without peace according to my gradual poor performance. To all candidates, best wishes in your exams. We shall meet again.”

According to the school headteacher, the student hadn’t performed poorly: “The information I have is that some children reported to his guardians that his academic performance was declining when they saw him become number two. But that is untrue because last time he was number one with 369 marks while this time round he was number two with 372 marks,” he said. The headteacher speculated that the boy’s problems might have emanated from home.

Whether or not this young boy truly died from suicide because of his results, isn’t it heartbreaking that a child would even consider 372 marks (out of a possible 500) as a failure?

This is just one example.

There are many others who take their own lives due to their perceived poor performance in school. Who’s responsible?

Parents, for instance, are known to have helped their children cheat in exams, to have bribed the system, or to completely subvert it. For example, they have registered their children to sit their exams in poor-performing schools, so as to take advantage of the quotas reserved for these underprivileged schools by prestigious secondary schools: Alliance, Kenya High, Maseno School, Mang’u, Starehe, Limuru Girls, are often amongst those most prized. Students resort to cheating in exams, after realizing their parents are also doing it.

Where did this obsession for ‘success’ through shortcuts, really come from?

I once spoke during a parents-teachers meeting for KCPE candidates and the on-going discussion was whether the candidates should attend classes on Saturday too during the holiday period. First of all, the Ministry of Education had already banned holiday classes, but several schools were doing it secretly. In addition, plus the assignments being given daily, they wanted the children to go to school on Saturday too.

‘When will these children rest?!’ I remember protesting.

Even if they’re examination candidates, it gets to a point where it is just too much for them too. How do we expect them to learn if we keep over-feeding them with information and assignments to a saturation point?

Only one other parent, a mzungu, agreed with me in the entire room, all rejecting my apprehensions. They all recounted how hard they had to work, relayed the pressure they endured during their time as students.

Then I was tempted to ask, ‘and how did that turn out for you? Are you happy with your life?’ But well, I decided against it.

Throughout the entire meeting, as the mzungu and I conversed, I could sense an air of disappointment, ridicule perhaps, coming from the parents’ present. An atmosphere that gave life to the old adage, ‘Coastal and white people often spoil their children.’

They proceed to talk about how life is challenging, and of the need to toughen up children so that they could deal. In my mind, I kept thinking, the economy and life in our country has always been tough since I could form any independent thought. That it is very likely that our children, including their own children, would also have to hustle hard so as to make it in life. But then again, why do we feel the need to put our children through the same dysfunctional system? Why do we need to make these ten, twelve-year-olds understand struggle at such a tender age? Why do we romanticize struggle and poverty and hustling and harsh environments like it is the ONLY way that we can ever succeed in life? Why do we make it seem like one needs to work fifteen to twenty hours a day, or even more, so as to make it in life?

What exactly constitutes making it in life anyway?

***

Stay tuned for the final part of this article. Thank you!

***

Also, my book ‘Reflection & Resurgence: A Believer’s Journey to Islam’ is available at 1500/= only. To get yours contact me at 0704 731 560